The Gras lamp, from workshops to art galleries

There are real epic stories in the history of design; pieces that have stood the test of time, the fruits of a clever blend of avant-garde, ingenuity and opportune encounters that have transformed everyday life and inspired the greatest architects. Created for workers in need of lighting in the noisy and dusty workshops of the first half of the 20th century, the Gras lamp has, over the decades, become a true icon of design, an object coveted by collectors around the world.

Genesis of an industrial success

A lamp without screws or welding, "dedicated to the humble task of bringing light where it should land to facilitate the work of the worker or the designer in the anonymous shadow of workshops and design offices" writes Patrick Favardin in his foreword to the book La Lampe Gras by Didier Teissonnière. This is how the story of this light begins.

After several fruitless works, Bernard Albin-Gras filed the patent for this articulated lamp for industrial use on October 13, 1921. A true innovation then, this light with variable geometry which plays the contortionists on its perfectly stable base fixed to the workbenches and architect's tables, supports the vibrations of the machines without ever going out of order.

The patent, passed from hand to hand, will allow the model to evolve. The inventor Louis-Theodore Didier Peyrot des Gachons isolate the electrical wire with a tube for safety advantage.

But this is in 1927, by partnering with Jean Ravel, that the Gras lamp is definitely on the rise. Available in several models, the success is immediate. The Gras lamp is on many offices of the civil service and even in the the operating room of the Île-de-France line. It will be producted by the company RAVEL, without major modification, for nearly fifty years, a remarkable achievement in the industry.

The architects’ lamp

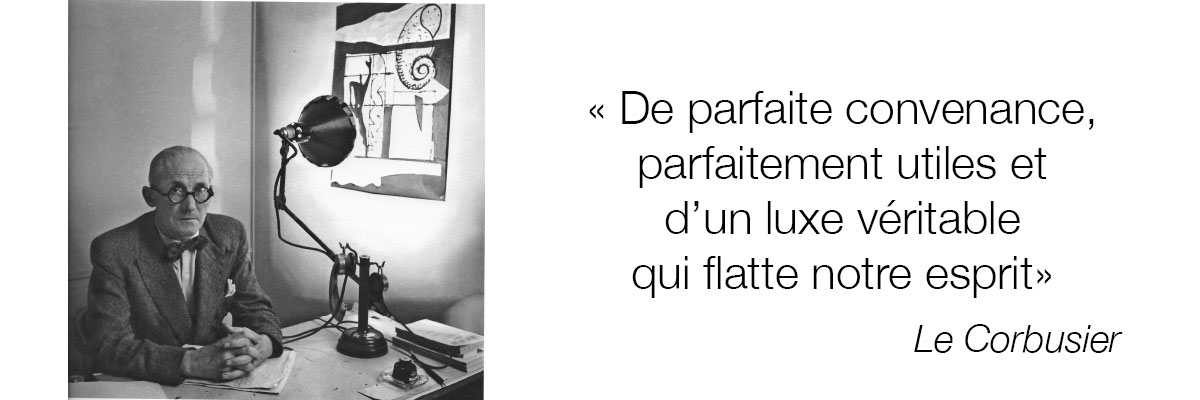

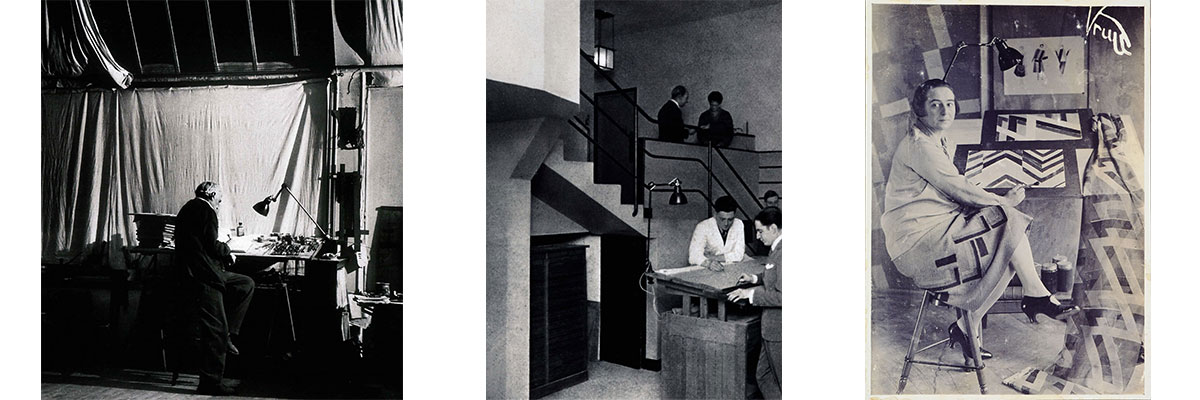

"Perfectly suited, perfectly useful and of a real luxury that flatters our minds" (Le Corbusier, The Decorative Art of Today), the Gras lamps quickly seduce Le Corbusier, who equipped his offices and private houses with them and will help get out of the workshops this lamp, first designed for industry and the service sector. Many other architects will take part in this worldwide success - Robert Mallet-Stevens, Eileen Gray, Michel Roux-Spitz, Saunia Delaunay or even Georges Braque.

A reputation that it owes to its simple and fully functional lines, without superfluous ornamentation condemned by its creator. Drawing at the service of the aim, the very essence of design.

Georges Braque, Paris 1946 Robert Mallet-Stevens, Paris 1927 Sonia Delaunay, Paris 1924

Nowadays - an iconic piece

The 1980’s sign the great return of the Gras lamp on the front stage.

Somewhat neglected because less essential in workshops where machines now integrate their own lighting system, it is amateur design lovers who will dust off the piece before Philippe Starck fully gives it its letters of nobility by bringing it into the contemporary history of interior architecture at Maison Lemoult.

The gallery owner named Didier Tessonnière has written a book, The Gras Lamp, and has created its Teisso gallery in Paris, where are shown the various model series but also prototypes and much rarer models.

Cover Page, La Lampe Gras Inspiration - Photos @Galerie44

Copied and recopied throughout the world, the Gras lamps are today edited by DCW editions which have exclusive rights, retaining the emblematic models which have built the legend of this light.

As for the vintage Gras lamps, which we particularly appreciate at the gallery for their avant-garde, they are a delight for collectors around the world, especially in France, Japan and the United States.

As Didier Teissonnière describes it very well: "This unexpected fate is indicative of the new look at the object. What matters now is its ability to osmosis with the principles of the “new spirit”. An object is real, and therefore morally acceptable, if its formal beauty is the product of its pure functionality, thus acquiring a kind of ideological innocence like the harmonious perfection of a pebble collected on a beach. "

Essential models

- Model 201 semi-fixed, the adjustable lamp for drawing tables

- Model 205 portable, the adjustable desk lamp

- Model 215 mobile, the floor lamp for clinics and studios